Note: This post is an excerpt from my book, Nice Bike: Making Meaningful Connections on the Road to Life. In fact, this is almost the entire last chapter of the book! And it’s a perfect post to honor our military veterans on Memorial Day weekend. I hope you enjoy it! — Mark

The Ultimate Nice Bike

From reading my stories, and learning about my friends, family, and business associates, I hope that you have gotten a clear understanding for what Nice Bike is all about. Using these two words provides the fuel to transform your organization and your life. Nice Bike will enable you to acknowledge, honor, and connect with those around you. Sometimes, all three happen at once. This is the real magic of Nice Bike.

From reading my stories, and learning about my friends, family, and business associates, I hope that you have gotten a clear understanding for what Nice Bike is all about. Using these two words provides the fuel to transform your organization and your life. Nice Bike will enable you to acknowledge, honor, and connect with those around you. Sometimes, all three happen at once. This is the real magic of Nice Bike.

My dad worked hard at the post office every day sorting mail. He was proud to be a part of the United States Postal Service. He always griped that UPS delivered boxes and “took the cream off the top.” Dad said, “Anyone can deliver boxes. Try sorting and delivering a couple of million Christmas cards every year, and we’ll see what they can do!”

Like a lot of dads of that era, he was always there for us, never missing a ball game or a school event. Unlike some dads I’ve seen at my kids’ ball games, my dad never yelled at the referees, complained to the coach about my playing time, or told the coach what play to run in a game. Win or lose, the most Dad would ever say was “good game.” I think this is a great lesson for parents. Support the child, and simply enjoy the game.

Dad and I didn’t do a lot of things together. We never threw a baseball back and forth. We never overhauled a ’57 Chevy or built a tree fort in the backyard. We went fishing once and hunting once. I remember both clearly, especially the pheasant hunting trip in Minnesota. I was twelve years old. We pulled up to a farmer’s field with a long ditch next to the road. Dad said, “Yeah, Mark, you go down to the ditch and kick around. If any birds flush, you hit the ground real quick.” At that point, I wished that we had owned a dog.

Dad and I did watch a lot of WWII movies together. He liked to watch these since he served in that war, so we would sit on the couch and watch them on our black-and-white tele-vision. Plus, if a first-run movie about the war was showing at the Paramount Theater in downtown St. Cloud, we jumped in the Ford to see it. To this day, I have a huge interest in WWII history because of the seed that Dad planted.

Love was displayed daily in how our parents were there for us—by working hard, caring for us, reading us bedtime stories, making sure we said our prayers, having great meals as a family every night at the table, and making a big deal out of holidays.

Love was popcorn and a soda pop on Saturday night. Love was slipping me an extra two dollars when I went out on a Friday night. Love was packing the family in the Ford and visiting the relatives for the day.

It was the little things that displayed love in our house. Dad loved being in the bowling league with his buddies. He bowled every Wednesday night, and when we woke up for school on Thursday morning, there would always be five bags of Old Dutch garlic potato chips on the kitchen table—one bag for each kid.

In our house, love was demonstrated by Mom’s hard work. I would play in the swamp not too far from our house and come home covered in mud. Mom just grabbed the garden hose, sprayed the mud off my jeans (while I was wearing them), and washed the jeans that night. Mom fixed the flats on our bike tires, typed our handwritten school papers, sewed our clothing, and pretty much ran the home without ever complaining or whining about any of it.

My parents balanced our upbringing with demonstrated love and clear boundaries. The boundaries were set curfews, church every Sunday, and proper behavior at the dinner table, such as our always asking, “May I be excused?” before leaving the table. Rules and guidelines were clear and enforced.

But as much as we were loved, we never shared the words “I love you.” It’s not that we didn’t feel it; we just didn’t say it. I don’t think we even said “I like you” that much. One day, I heard a speaker by the name of Leo Buscaglia, the author of Living, Loving and Learning. Buscaglia encouraged his listeners to tell the people who mean the most to them—especially their parents—how much they’re loved. That one really hit me because as an adult, I realized I had never shared those words with my parents. I said, “I love you,” to my wife and children daily, but I had never said it to my parents.

I don’t know why, but it wasn’t easy to say it to Mom and Dad. The words should have flowed out of me, but it was difficult to tell my parents—out loud—that I loved them. I saved the moment for Christmas Eve, which was always my parents’ favorite night of the year. The rest of the family was in the kitchen, and Dad was in the living room sitting in his chair.

“Dad, do you have a moment?” I asked.

“Ya,” he replied.

“Well, Dad, it’s just that you never missed a game I played, and you never yelled at the refs or talked to the coaches, and we did go hunting that one time . . . and . . . well, I . . . uh . . . I love you, Dad.”

“Good. Tell your Mother.”

That pretty well covered it. Granted, it got easier after that first time, and before long, every conversation ended with “I love you, Dad” and a quick return of “Love you, too, Son.”

I knew a lot about my parents, Nubs and Aggie, but not as much as I should have known. Like a lot of kids, I took a lot for granted and never looked for heroes in my own home until I got older. A turning point for me was in the 1980s when I attended the funeral of a friend’s parent. He had lost his other parent about a year earlier. His advice given to me in the funeral home really hit home: “Hey, buddy, ask your folks some questions.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“The little stuff that you can never know once they’re gone. How they met, where they honeymooned, who their favorite teacher was, what their first job was, what their favorite book was . . . the little stuff that captures who they were. Once your parents are gone, the library is closed.”

That statement really got to me. So, I started asking my parents some questions. I knew my mom had grown up on a farm in Eden Valley, Minnesota, but I didn’t know that she had gone to school in a one-room schoolhouse for eight years with thirty-five other kids, or that Grandma Anna was one of the first teachers at that same school. As a young teacher, Anna boarded in a room at a local farmhouse where she met a young farmer named Jim whose family owned the house. They married a year later.

I knew that my dad had served in the Navy in WWII. I can’t tell you how many Saturday mornings I spent at the local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) club. On Saturday morning, I would go grocery shopping with my mom and dad. As soon as we hauled in the last bag of groceries and placed them on the kitchen table, Dad would turn to Mom and say, “Aggie, I’m going to the VF.”

VF was short for VFW. Why Dad had a need to abbreviate that one, I don’t know.

“Well, Nubs,” Mom would say, “if you’re going to the VF, at least take the boy with you.”

You see, I was the fourth born in a family of five, and I was the youngest for ten glorious years before my younger brother, “Oops,” was born. (Actually, his name is John, and he turned out to be the crown prince of the family.) Dad would drive me to the VFW, and he’d always order a Grain Belt beer on tap while I had my favorite—a bottle of Orange Crush. All of the guys would be there—Ron Gruber, Leo Satzer, Lenny Keller, Cliff Eisenreich, Bud Streitz, and Woody Bisset. To me, these men were bigger than life. They always made me feel welcome as I sipped my Orange Crush and listened to them talk.

But as a kid, I never knew that these were the same guys who served in WWII. I didn’t know that these were the men who attacked Omaha Beach on D-Day. I didn’t know that these were the men who froze in the foxholes and held on during the Battle of the Bulge. I didn’t know that these were the men who hit the volcanic sand of Iwo Jima or survived the Bataan Death March. I never knew, because they never talked about the war. Never.

They talked about their families, their work, or the Vikings and the Twins. They spent one entire Saturday morning discussing the art of properly sealing a toilet with a wax ring, complete with illustrations on a bar napkin. But they never talked about their war experiences.

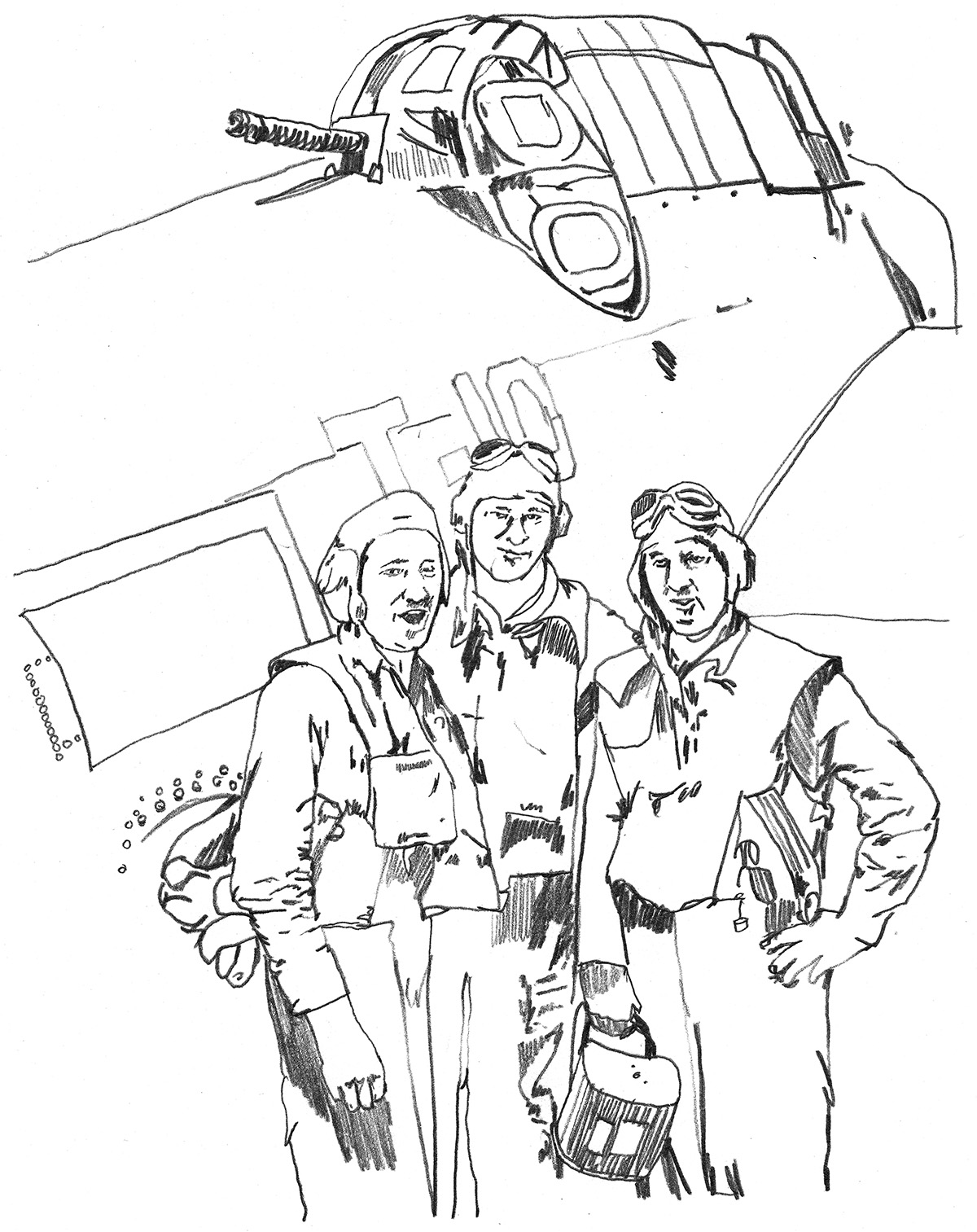

Once I finally started to ask the right questions, I discovered that my dad had served on the aircraft carrier USS Lexington. He flew with a crew of two other men in a plane called the TBF Avenger, a torpedo bomber. The crew was made up of a pilot, a turret gunner, and a radioman/ventral gunner (under the tail), which was used to defend against enemy fighters attacking from below and to the rear. Dad served as the radioman/ventral gunner. His crew landed on the deck of the Lexington ninety-seven times in training and combat missions.

“The very first time we landed on the Lex,” Dad told me, “the seas were rough, and the ship was heaving up. We came in too fast, and we hit so hard that it blew out the tires on the plane.”

“What did you think at that moment, Dad?” I asked him.

“I thought it was going to be one long war.”

Dad’s hometown newspaper, the St. Cloud Daily Times, carried this paragraph in 1945 about their hometown son: “Norbert Scharenbroich home on leave, is a crewman of air group 30, which destroyed or damaged 219 Japanese aircraft and 51 ships during five months combat aboard an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, at a loss of three pilots killed and five wounded.”

Dad kept a journal during part of the war that I found after his death. He wrote warmly about turret gunner Austin “Jonesy” Jones from Florida and E. C. Knospe from St. Paul, who was the pilot and “a good egg.” Dad had entries for almost every day up until they did a bombing run on the island of Truk in the Pacific. On the return from their bombing run, they had to ditch in the ocean, and the pilot died in the water. Dad’s last entry was: “War is hell.” He didn’t write another word in the journal after that.

A Plane Ride with Dad

From my questions, I found out that Dad hadn’t been in an airplane since WWII. I’m on a flight almost weekly due to my speaking career. So, in 1984, I invited my dad to take a trip with me to Washington, D.C. I was giving a big speech. In fact, I was sharing a stage with First Lady Nancy Reagan. Well, she spoke the day before me, but it was the same stage!

I begged my mother, “Please, Mom, make the trip with us.”

But she couldn’t be persuaded. “No, Mark, I just don’t want to go. Take your father, and do me a favor.”

It was a great trip. My dad enjoyed my presentation, and we toured the city together. The last monument we planned to visit was the Lincoln Memorial. We ended up there late in the evening. Other than Abraham Lincoln, it was just my father and myself standing there that night. It was a very powerful moment when we sensed the greatness that this country was built on.

We left the Lincoln Memorial around 11:00 p.m. and took a left along the Mall. In just a short time, we came upon the Vietnam Memorial. It had only been there for a few years at that time. The first thing that came to my mind was the number 256. That was my lottery draft number from the Vietnam War.

A lot of men volunteered to serve, and a lot of men were drafted to serve. 58,178 names are engraved in polished black granite on the Vietnam Memorial. The first American soldier killed in the Vietnam War was Air Force T-Sgt. Richard B. Fitzgibbon Jr., and the last was Kelton Rena Turner, an eighteen-year-old Marine. He was killed in action on May 15, 1975, two weeks after the evacuation of Saigon.

With the exception of the return of our prisoners of war, those who came home from their service in Vietnam weren’t welcomed home with parades. Unlike the WWII returning soldiers, there were no cheering crowds of people or banners hung throughout their towns. When I ask Vietnam veterans to tell me about the toughest part of the war, many of them say, “coming home.”

As my dad and I were walking along the memorial, we noticed two Vietnam vets standing close to the wall. They were wearing their Army jackets and silently staring at the engravings of the names of their fellow soldiers. My dad slowly walked over to the two men and said, “Excuse me. Were you fellows over there . . . Vietnam?”

“Yeah. Yeah, we were,” said one of the men. After a long pause, my dad said, “Thank you, fellows. Welcome home.”

“Sir, you are the very first person who has ever said thank you to me for serving my country. That means a lot, man.”

At that point, the Vietnam vet moved closer to my dad and gave him a big bear hug. Then, the other Vietnam vet did the same. My dad was not known as a hugger, but he gave a big hug back to each man. I noticed tears in the eyes of the Vietnam veterans and in the eyes of the WWII veteran—my father. That was the first and last time I ever saw tears in my father’s eyes.

Dad acknowledged the Vietnam vets, honored their service, and connected with them on a very personal level. It’s a moment I will always cherish. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the ultimate Nice Bike.

Acknowledge, honor, connect, and you will change the world, one person at a time.

Nice Bike, Dad.

Leave A Comment